Protein is a cornerstone of nutrition, but not all protein sources are created equal. You’ve likely heard the terms “complete” and “incomplete” proteins tossed around in health circles, especially when comparing animal-based and plant-based diets. But what do these labels really mean and how much do they matter when it comes to everyday eating?

This guide breaks down the science behind protein quality, explains how to meet your amino acid needs, and offers practical tips for building meals that support energy, recovery, and long-term health.

What Makes a Protein “Complete” or “Incomplete”?

Proteins are made up of amino acids some of which the body can produce, and others that must come from food. These are called essential amino acids, and there are nine of them.

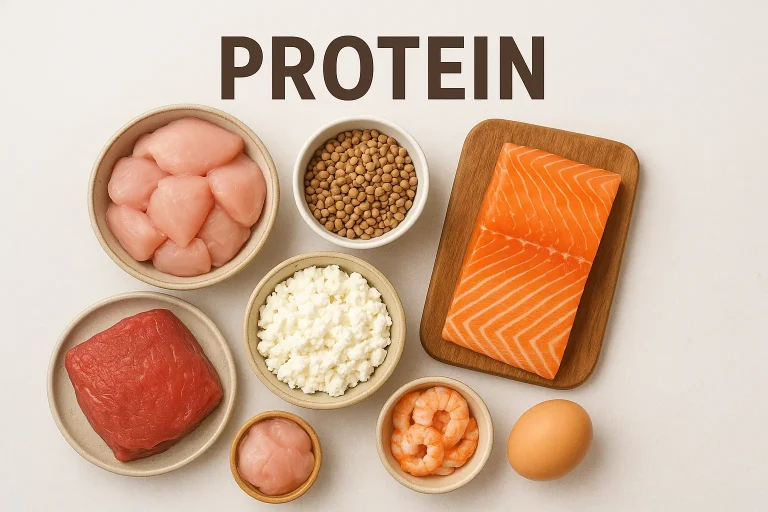

A complete protein contains all nine essential amino acids in sufficient amounts. These are typically found in:

- Meat, poultry, and fish

- Eggs

- Dairy products

- Soy products (e.g., tofu, tempeh, edamame)

- Quinoa and buckwheat

An incomplete protein lacks one or more essential amino acids or contains them in lower amounts. These are common in:

By signing up, you agree to receive emails from RealFit Wellness. You can unsubscribe anytime. See our Privacy Policy.

Your Weekly Wellness Boost

- Grains

- Legumes

- Nuts and seeds

- Vegetables

Incomplete proteins aren’t “bad” they just need to be paired strategically to ensure the body gets all the amino acids it needs.

Why Protein Quality Isn’t Just About Labels

While complete proteins offer a full amino acid profile in one source, that doesn’t mean incomplete proteins are nutritionally inferior. The body is capable of combining amino acids from different foods over the course of a day to meet its needs.

This concept is known as complementary proteins. For example:

- Rice (low in lysine) + beans (high in lysine)

- Whole wheat bread + peanut butter

- Lentils + quinoa

You don’t need to combine these foods in the same meal just include a variety of protein sources throughout the day. This approach is especially useful for those following plant-based diets.

How Much Protein and What Kind Do You Really Need?

Protein needs vary based on age, activity level, and health goals. The general recommendation for adults is:

- 0.8g per kg of body weight for sedentary individuals

- 1.2–2.0g per kg for active individuals or those aiming to build muscle or lose fat

When it comes to protein quality, the focus should be on:

- Total intake across the day

- Variety of sources to cover all essential amino acids

- Digestibility and bioavailability, which affect how well the body absorbs and uses protein

Animal proteins tend to be more bioavailable, but plant proteins can be just as effective when consumed in diverse combinations.

Building Balanced Meals with Mixed Protein Sources

Creating meals that support your protein needs doesn’t require perfection just a bit of planning. Here are some simple ways to include both complete and complementary proteins:

Breakfast:

- Scrambled eggs with whole grain toast

- Overnight oats with chia seeds and almond butter

- Tofu scramble with vegetables and quinoa

Lunch:

- Grilled chicken salad with chickpeas and avocado

- Lentil soup with whole grain bread

- Brown rice bowl with black beans and roasted vegetables

Dinner:

- Baked salmon with sweet potato and steamed greens

- Stir-fried tofu with soba noodles and sesame seeds

- Chickpea curry with wild rice and spinach

Snacks like Greek yoghurt, hummus with whole grain crackers, or trail mix with nuts and seeds can also help round out your daily intake.

What Actually Matters for Long-Term Health

Rather than stressing over whether every meal contains a complete protein, focus on the bigger picture:

- Eat a variety of protein-rich foods throughout the day

- Include both animal and plant-based options if your diet allows

- Pay attention to portion sizes and overall nutrient balance

- Support your protein intake with fibre, healthy fats, and complex carbs

Protein quality matters—but it’s just one piece of the puzzle. A well-rounded diet that includes diverse sources will naturally provide the amino acids your body needs to thrive.